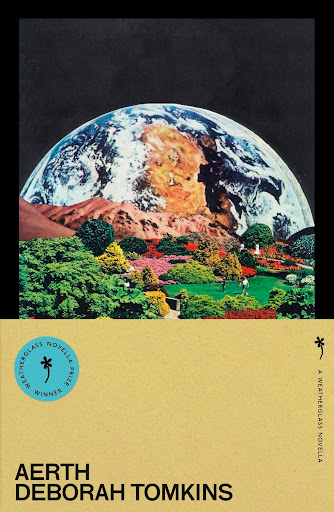

This month, novella-in-flash.com features an interview with the writer Deborah Tomkins. Deborah’s novella-in-flash Aerth was published by Weatherglass Books in January this year. It has already sold out of the first print run and has been reprinted.

Michael: Welcome to this blog series, Deborah. It’s been so exciting to see how your novella has been well received in early reviews, including in broadsheet newspapers such as The Guardian and The Telegraph, as well as by book reviewers on Youtube and Instagram. Especially as it’s one of those rare things – a genre-based novella-in-flash (with speculative, and science-fiction, and climate fiction elements). I am very much hoping your success inspires more flash fiction writers to try writing genre-based novellas.

I think the tale of this book’s journey to publication is worth re-telling to readers, as it strikes me – from the outside – as an inspiring story of never-give-up determination.

You’ve talked about how a version of this book was first longlisted in 2019 in the Bath Flash Fiction Award Novella-in-Flash competition. And you kept working on it for several years before submitting it to the Weatherglass competition. Could you talk a bit about that journey? Were there any particularly difficult moments along the way? And also what lessons you might be taking from the process, for your future writing projects?

Deborah: Thank you so much, Michael, and thank you for inviting me onto the blog series too.

It was quite a journey. It ended up being about 5 years, from first seeing if I could write a novella-in-flash (and flash fiction itself was still very new to me back in 2018, when I began this story) to finally sending it in August 2023 to Weatherglass Books for their Inaugural Novella Competition, which was judged by Ali Smith. That last year or so I didn’t do much to it, actually; it just sat in my computer and I occasionally sent it off to a publisher or a competition.

There were lots of difficult moments! Novellas are quite difficult, and a novella in flash is not only difficult but also very slippery, in the sense that these tiny ideas that you have may take the story in any number of directions – and they did. It’s not easy choosing what to keep and what to throw away (although I think no writing is ever wasted – you’re always learning what works and what doesn’t), or working out what direction is the most fruitful one for the story, or what will be most surprising to a reader. And as a writer I found I was too close to see that clearly, so the long process was very helpful – leaving it for several months and going back to it with fresh eyes.

I kept thinking about it, though, and even when I thought it was “finished”, I would go back to it and play around with it some more, particularly when it hadn’t been accepted somewhere. The story – and Magnus, my protagonist – wouldn’t leave me. I kept feeling that it was a deeper and stranger story than I had been allowing it to be.

I’ve also realised that I’m not a fast writer. I need to spend a lot of time with a story, to see what it might be saying or where it may want to go.

Michael: It’s really interesting that you noticed an urge to make the story deeper and stranger. My hunch is that for so many novella-in-flash manuscripts “deeper and stranger” would be a very productive instinct to follow! And personally rewarding and fun for the writer during the process, too.

I want to ask you next about the genre-based elements of this novella-in-flash. If we think about Aerth’s qualities as a piece of “climate fiction” first of all: you’ve been involved in writing about the environment for some time – for example via Bristol Climate Writers, and also in other contexts. I’m wondering what questions (about climate, or environment, or ecology) you particularly wanted to explore as you wrote it? And I’m also interested, with this piece of climate fiction, in how you saw the roles of the novella’s three different story-worlds (not only the twin planets of Aerth and Urth, but also Mars, which features too), which each have such different qualities as settings?

Deborah: In many ways this book came together accidentally, in that I didn’t have a plan at the start. It was very much not plotted! I wrote small pieces – or fragments of pieces – as they occurred to me, and as I was thinking about Magnus and his life. The very first piece was one I wrote in a workshop at the Flash Fiction Festival in 2018, and comes about a third of the way through the book.

But, like most of us, I have my preoccupations – in my case, climate, ecology, and ethics – and these began to show more clearly as I explored Magnus and his world. After a while it became so obvious that I was writing about climate that I simply went with it. Magnus’s own planet Aerth is heading towards an ice age, and I thought it would be interesting to explore how a modern technologically advanced society coped with the challenges of this. Our own planet Earth should right now be cooling down, coming to the end of the current interglacial period, rather than heating up. And, counter-intuitively, in the future because of the rapid heating of our planet, the vast ocean currents in the Atlantic that keep Europe temperate may just switch off, in which case we will become as cold as northern Canada. This has been known for a long time, but is only now reaching the media. The reader can decide which scenario is playing out here.

Aerth is also pristine. It’s unpolluted, deeply forested, and there is an abundance of wildlife – as there was on our own planet only a couple of centuries ago – due to the small population and their resolve to “Do No Harm”. What would it be like to live on a planet teeming with life?

Urth – Earth’s “dark twin” on the other side of the Sun – is entirely opposite. On this planet anything goes – ethics are optional, the planet is heating very fast, it’s polluted and aggressive, and there is little wildlife left. Magnus becomes trapped there and has to navigate a society he is ill-equipped to deal with, as his home planet is deeply ethical, kind and respectful. Here I was exploring a kind of future that we want to avoid.

Mars was a kind of airlock! As a child Magnus always wanted to travel there, and he manages this – but the lure of exploring Urth pulls him on. For me, Mars was a very brief interlude in which I considered the difficulty of “terraforming” a dead planet – although in this case Mars is not entirely dead as it has a thin atmosphere. There has been a lot of talk about colonising other planets in recent years, in part to rescue humanity from destruction, but I honestly think it would be far better to look after the one we have.

All the flashes were written out of order, and I spent a long time working out how to order them. My editor and I sometimes had different ideas!

Michael: Fascinating! I really like how you describe this novella-in-flash coming together “accidentally”, as you accumulated the fragments. I think readers will draw inspiration from the fact that you were patient in exploring the main character (and his story-world) from different angles until the novella started to take clearer shape. Could we also talk about the book as a piece of “speculative fiction” or “science-fiction”? I noticed that Luke Kennard in The Telegraph described the book as “more allegory than hard sci-fi” yet concluded: “an intelligent sci-fi thriller and a thought-provoking parable”. Were there scientific aspects that you had to research, in order to deliver a convincing fiction? Were you consciously thinking of it as allegory or parable? Or did you see it as a piece of “speculative” writing? Which non-realist elements did you most enjoy experimenting with and dreaming up?

Deborah: I would very much agree that it’s not hard science fiction! However publishers have to give readers an idea about a book’s genre, and “science fiction” is close enough. I used to describe it as speculative. But really it’s neither of those things, nor is it fantasy. I recently came across the term slipstream, and I think it may be that, completely unwittingly! Aerth doesn’t sit squarely in any genre category, really, and I think flash fiction can be fairly literary, in its use of language and form, the not-always-obvious ideas, and so on.

As I’ve been an environmental campaigner for many years, I know a fair amount about climate science and environmental issues (although I’m not a scientist). So it wasn’t too difficult for me to subtly weave that kind of information into the story, as I think about it a lot in my day-to-day life.

I did have a lot of fun messing with physics! The whole conceit of two planets on opposite sides of the Sun is an ancient idea, first invented by the Greeks. I love the idea – but sadly it’s not true. We would have spotted another such planet long ago, because of gravitational pull and light bending around objects in space. I believe one of the space probes had a look-see a few years ago – and Urth is definitely not there (neither is Aerth). My protagonist Magnus also experiences strange phenomena which are pretty unlikely… shimmering doors and doppelgängers, for example. I really enjoyed playing with these ideas, which veer into fantasy, I suppose.

I didn’t consciously think of this story as allegory or parable, although I’m delighted with Luke Kennard’s assessment. I think many writers write for themselves first of all, and I was exploring different ways of living. What would it be like, to live in a society where the most important law is to “First, do no harm”? And where did that law come from? And then to explore the opposite, where the imperative not to harm never crosses people’s minds. I was able to play with these ideas over several years as the book very slowly came together.

Michael: Great to hear this about your process, Deborah. I think it’s inspiring that your book was about “exploring different ways of living”. There’s lots to take from that. And good for more people to know about “slipstream”. Thank you for participating in this blogpost series!

Deborah & Michael: To finish, we’d like to leave you with a writing prompt that we’ve created together:

Invitation: Write a flash fiction from the point of view of another species (or non-human perspective), observing one of your novella’s main characters.

- What is the human main character doing? (Think about what’s physically observable from the non-human perspective).

- What does the other perspective understand (or not) about the human’s behaviour?

- How do they feel about what’s happening?

- Are they able to react, or interact with the human main character? If so, how?

- Does the main character notice being observed, or is it happening without their knowledge?

- Finally, what insight, question, or truth about humanity might the story move towards?

Food for thought #1 – by Craig Raine

Food for thought #2 – by Helen Moore

Food for thought #3 – by Caleb Parkin

Deborah Tomkins Biography – Deborah writes long and short fiction, often about human relationships with the natural world. Her short fiction has been published online and in print. Her novella-in-flash Aerth (Weatherglass Books, January 2025) won the Inaugural Weatherglass Novella Prize, judged by Ali Smith. Her forthcoming novel The Wilder Path (Aurora Metro Books, May 2025) won the Virginia Prize for Fiction in 2024. In 2017 she founded the local writers’ network Bristol Climate Writers.

Website: deborahtomkinswriter.com

Bluesky: @tomkinsdeb.bsky.social

Other flash fiction by Deborah Tomkins: www.deborahtomkinswriter.com/stories/

==================================

Don’t want to miss this blogpost series? Sign up to receive each new post direct to your email in-box (and get access to exclusive offers on mentoring) here:

Are you working on a novella-in-flash? Or wanting to write one? Find out more about Michael Loveday’s Novella-in-Flash mentoring: here.