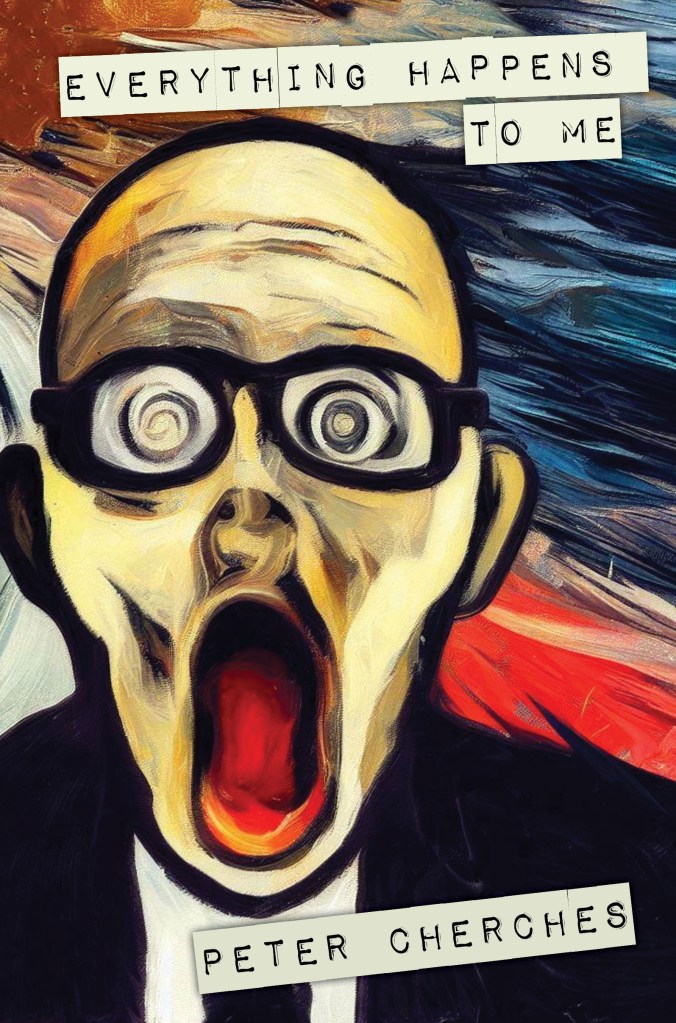

This month, novella-in-flash.com features an interview with the writer Peter Cherches, whose darkly absurdist novel-in-episodes Everything Happens to Me, which chronicles the bizarre yet everyday misadventures of a Brooklyn-based fiction writer, was published by Pelekinesis on 12th September.

Michael: Welcome to this blog, Peter, and congratulations on a remarkable new book. I’d like to start by asking you about one of the characters in it. At the centre of this novel composed of short-short stories is the figure of a first-person narrator, named Peter Cherches, apparently an alter-ego for the author (such are the uncanny similarities of his life – as writer and New York resident – to yours); the next most prominent character is the narrator’s unnamed neighbour in the apartment block where they are both residents.

Although the character of the narrator constitutes the foreground of the novel, it was actually the role of the neighbour – who pops up in so many of the chapters, in a variety of contexts – I became strangely fascinated by as I read through your book. I’d love to hear you talk more about this figure of the neighbour: what were the origins of writing about this character? What was it that interested you in the idea of the neighbour, and the particular dynamics of this narrator’s relationship with him?

Peter: The neighbour is actually based on my real-life next-door neighbour of 35 years. We do indeed have a strained relationship, and my portrayal of him is probably one of the most realistic aspects of the book. He plays the double role of antagonist and doppelgänger, so I wanted him to remain nameless, generic. Plus, it gives me plausible deniability. Many of the chapters are based on the protagonist-flâneur’s oddball encounters with a wide range of individuals, and the neighbour acts as a grounding constant.

The neighbour stories started out as a parallel project to the other work in the book and was originally intended as a separate volume. But after a while it became clear that the two groups were really of a piece, and the neighbour stories spread throughout the book acted as a kind of glue to give the overall project a narrative arc. The only other recurring character, Mrs. Papadopolous, is seemingly minor, but for me the few pieces in which she appears further shape the narrative, especially toward the end. Sequencing is always of utmost importance for my books, but in this case I hope it really does make a unified entity out of many individual pieces.

Michael: And how did you assess the sequencing? I’m imagining that it could have been especially challenging with a novel composed of 90 relatively miscellaneous short-short stories. A term I’ve previously used to understand this kind of novel-in-short-short-stories is the “novel-as-collection”, where there isn’t really a cause-and-effect kind of plot development (in which one incident leads into another), but instead what would otherwise be relatively standalone stories are given some kind of gentle tethering so they cohere – often through a recurring central character or two, and/or perhaps a common setting for the stories, and/or some recurring motifs for a more subtle “binding” effect (in the case of Everything Happens to Me, I might see the latter as things like the narrator’s occasional visits to restaurants/descriptions of food, references to jazz and popular song, encounters with childhood friends and old acquaintances, recurring doppelgängers, and so on). What was your guiding process for figuring out the order of these stories, when many of them might look – on the surface – like they could potentially appear in a different order if you’d wanted them to?

Peter: Sequencing any collection is a balancing act, but here, once I started considering the novelistic possibilities of this particular group of pieces, sequencing became of primary importance. While there is no traditional plot development, I wanted to nonetheless give a feel of forward motion. To that end, one of my sequencing strategies was a kind of poetic chronology; that is, while the pieces all take place in a generally sensed present, stories that harken back to childhood appear early in the book, and the end of the book brings intimations of mortality. Then there are the neighbour stories, which account for maybe 20% of the book. I wanted to spread those out at relatively equal intervals, with some earlier pieces introducing the character and the relationship, and later pieces building upon that relationship. The text is deliberately framed by two neighbour stories. As you’ve mentioned, there are also a number of other recurring themes and settings. In some cases there are several quite similar pieces that would come off as bafflingly repetitive if placed in close proximity, but, hopefully, carry a haunting resonance when peppered throughout the book–story doubles that echo the character doubles. In this book, as in much of my work, there’s a prevailing mood of anxiety and frustration, and I think those repetitions bolster that mood.

The sequencing and final edits were a simultaneous process. As many of the chapters were originally published as stand-alone stories, there were, for instance, duplicative setups and explanations that could be cut from some of the individual pieces.

Michael: About that “prevailing mood of anxiety and frustration” – in a number of stories in the book, the narrator enacts the role of a consumer – going into shops and restaurants, phoning up company helplines, and so on. The cumulative effect was that he seemed to me to represent a kind of frustrated or oppressed consumer in particular. Oppressed by contemporary capitalism, one might perhaps say, in its various manifestations? But in quite a comical way. A waiter denies that a pigeon has shat on the restaurant table. There’s a customer helpline for a utility company where the junior assistant says, in that apologetic yet oh-so-recognisably patronising way: “There is nobody with more authority.” The narrator orders a burger that’s branded the ‘Well-Beyond Impossible Burger’ and the burger doesn’t exist [second story at this link]. He calls the number in a Craigslist ad and it seems like a trap. And then there are many other ways in which the narrator seems absurdly persecuted by a malign universe: gross intrusions into his privacy, ransom notes, gossiping neighbours in the building where he lives, etc. Did you have a vivid sense, when you set out to write this book, of wanting the narrator’s “anxiety and frustration” to arise specifically – in an absurd and comical way – from the systems of modern life that surround him as a citizen-consumer, and that seem to confound and persecute him? And how does this chime (or not) with your own personal view of 21st century living?

Peter: It’s much more pedestrian than that. For me the physical marketplace is one of the richest sources of interpersonal interaction and offers a variety of settings. My own daily activities and lifelong neuroses animate the character who shares my name, and these days, since retiring from my day job, much of my time is spent walking around Brooklyn and taking a daily restaurant lunch, hence lots of restaurant stories and street encounters. [Photo credit: Elder Zamora]

Those familiar settings allow me to imagine and flesh out the encounters that start out seemingly normal and then take a surreal turn.

I think that “surreal turn” is the core of these stories, and it’s a mode I’ve developed over the years, beginning with a series of stories literally drawn from nightmares, in the 1980s, a rich source of frustration and anxiety. By taking those dream memories and forming them into coherent narratives, I developed strategies for keeping the disjointed, disturbing mood of dreams in a more logically constructed story. Eventually, I started creating my own nightmares. Incidentally, as an undergraduate I studied playwriting and dramatic literature, and was completely smitten with Strindberg’s A Dream Play.

I further developed this style in public, online. I joined Facebook in 2013, and I got the idea of posting odd first-person stories that at first appeared to be normal status updates. It was a perfect laboratory in which to develop my timing–how much normal do I give before things turn weird ? The comments told me when I was really suckering the reader in. Of course, when you pick up a book labelled “fiction” you’re not going to have that same experience, but the stories’ effects still are dependent on those same technical underpinnings.

While I’ve occasionally written politics-fueled pieces, usually in a satiric vein, there’s little that’s blatantly political in this book, except where the politics is at the core of the character’s anxieties, like his fear of a visit from the police.

As far as 21st-century capitalism is concerned, technology has reduced those commercial opportunities for being physically among the public, and I think that’s sad; I miss all those hours I used to spend poring through the bins at record stores. [Photo credit: Elder Zamora]

Michael: Those are really helpful insights into how fictional narratives can emerge from a writer’s unique process. You’ve been associated with “the short-short story” for many years, and are seen as one of the key figures behind the contemporary prevalence of it as a literary form. How do you feel about the mid-1990s emergence of the label “flash fiction”, which now seems to have taken hold as a primary descriptor for the form. Is it one that you readily identify with?

Peter: I suppose flash fiction is OK as shorthand, but I don’t love the term. I’ve always preferred “short prose,” which doesn’t make a fuzzy or arbitrary distinction between short-short story and prose poem, or even poetic essay. Most of what I see published as flash fiction tends to be shorter versions of the traditional short story, miniatures in the Chekhov through Carver lineage

I think a good number of us in the States who were doing short prose before the coinage of terms like sudden fiction and flash fiction–for specific anthologies, originally– came more out of a fabulist or surrealist tradition–the Kafka, Michaux, and Borges lineage–writers like Peter Wortsman, Lydia Davis, Russell Edson, Marvin Cohen, and Barry Yourgrau, for instance. [Photo credit: Scott Friedlander]

Michael: That’s a really interesting observation about two lineages and traditions. Here’s a final question: I’ve always observed via your social media posts that you have eclectic reading tastes in the field of “short prose”. Could you leave readers of this blog with a list of recommended books they could explore, within the broad category of the “novel (or novella) in short episodes”, or novel-in-flash, or novel-in-short-short-prose, however it might be defined?

Peter: I love to evangelise about books, especially neglected ones. I’ll start with a cluster of titles that were extremely influential on me–Henri Michaux’s A Certain Plume and several works that run with Michaux’s premise, the adventures and observations of a somewhat cartoonish everyman who views the world with an idiosyncratic eye. Julio Cortázar’s A Certain Lucas is clearly an homage to Plume, and Calvino’s Mr. Palomar shares the approach. My own prose sequences inspired by these, “A Certain Clarence” and “Mr. Deadman,” both appear in my collection Lift Your Right Arm. But for Calvino my strongest recommendation is Invisible Cities, and for Cortázar Cronopios and Famas.

Nathalie Sarraute’s Tropisms is often cited as the opening salvo of the Nouveau Roman movement. One might call it an anti-novel or one might call it a collection of prose poems. It’s certainly anti-character; if I remember correctly there are no proper nouns. Rather than plot or character, what makes the whole greater than the sum of its parts are what the author calls “inner movements,” which “slip through us on the frontiers of consciousness in the form of undefinable, extremely rapid sensations.” Written in a spare yet poetic style that concretizes her abstractions, it’s a remarkable work, especially considering it was composed in the 1930s. I may have been unconsciously inspired by Tropisms when, in 1980, I wrote my first minimalist prose sequence, “Bagatelles,” where the two characters–named I and she–are virtual stick figures with attitude.

This might be a surprising choice, but Sinclair Lewis’ Babbitt differs from his other novels by building up a narrative largely from set pieces of varying length, an approach shared by another favourite writer, Evan S. Connell in Mrs. Bridge and Mr. Bridge.

I’ll close with two remarkable minimalists. Kenneth Gangemi’s best known book is the “novel” (I think it’s only 60 or so pages) Olt, but his The Volcanoes from Puebla is a travel narrative of a motorcycle trip through Mexico told in a bunch of short sections on various topics, presented alphabetically, like an encyclopaedia. Also brilliant is his novel The Interceptor Pilot, which takes the form of a film script.

Toby MacLennan has only published three small books of prose over a six-decade career; she works primarily as a multimedia artist. Her 1 Walked Out of 2 and Forgot It, published in 1972 by Dick Higgins’ legendary fluxus-adjacent Something Else Press, is wonderful, mysterious, and sui generis. I don’t know how else to describe it except that it’s perhaps a literary equivalent of Magritte’s paintings. The individual pieces range from one sentence to a half page. There’s plenty of blank space. She calls it a novel. Unfortunately, it’s long out of print and difficult to find. But her excellent 1996 collection Singing the Stars is still in print from Coach House Books.

Peter Cherches Biography – Called “one of the innovators of the short short story” by Publishers Weekly, Peter Cherches has published five full-length fiction collections as well as a number of chapbooks and several nonfiction books. Since 1977, his work has appeared in scores of magazines, anthologies and websites, including Harper’s, Fence, Bomb, Semiotext(e), North American Review, Fiction International, and Billy Collins’ Poetry 180 project. He’s also a jazz singer and lyricist. For more information on Peter, you can access his Facebook Author Page here.

==================================

Don’t want to miss this blogpost series? Sign up to receive each new post direct to your email in-box (and get access to exclusive offers on mentoring) here:

Are you working on a novella-in-flash? Or wanting to write one? Find out more about Michael Loveday’s Novella-in-Flash mentoring: here.